And I'd like to see that change. <Cue ominous music...>

Much of the current literature on science education points to "inquiry" as a best practice for teaching science. Inquiry-based science teaching is much more open-ended than traditional science instruction. It welcomes students' questions; in full-blown inquiry settings, students set much of the agenda for how they will explore and investigate and come to deep understandings about science concepts.

Recognizing that most of my college students didn't experience inquiry-infused classrooms in elementary school (or even in high school), I love to do science with them--practicing inquiring--and then analyze the activities we do. Hopefully this gets them to think deeply about why we do what we do...and not have them simply teach as they were taught. (This past week, we did "The Milk Lab" as an example--you can check out the basic idea here; it's super fun! Good conversation afterward too about the nature of science, their experience with science in school, what they noticed about me as a teacher in an inquiry setting, and what they noticed about their own thinking and behavior during this activity. Pretty gratifying as a teacher!)

This isn't new stuff for me, really. I started striving for a more inquiry-infused science classroom back around 2003-2004 or so, and I even wrote a few things about teaching science this way to encourage my colleagues in education. What follows is the text of an article I originally had published in 2009 in Christian School Teacher, a now-defunct publication of Christian Schools International. You can view the original article here on the archive of their blog site.

It’s the second week of school, and my 7th graders are busy in the science lab. One pair of students is carefully measuring exact amounts of water with a graduated cylinder before dumping them out on the tiled floor and mopping up. Another pair is pouring maple syrup on squares of carpet and then trying to scrub them clean. A third group is weighing a bucket of pea gravel from the playground. The duo in the corner has their rulers and calculators in hand to measure distances, compute surface areas, and determine unit costs. What’s going on here? Why so many different activities going on all at once? Why would I put myself through this controlled chaos? Actually, it’s an endeavor in engaging students in an inquiry-infused science activity.

What is “Inquiry?"

“Inquiry” is a huge buzzword in science education. While there are a great many possible ways to define inquiry in science class, I prefer to use the following: “Engaging students in discovering the wonders of creation by seeking answers to scientific questions.” I am convinced that the purpose of teaching science in Christian schools is to open students’ eyes to wonder at the creation, and thereby stand in wonder of the Creator as well. I have also become convinced that teaching students to ask scientific (that is, testable) questions is an extremely engaging way to do just that. I’m learning, more and more, how to put this definition into effect in my own teaching practice. This has meant, however, that I’ve changed the way I think about what happens in my science classroom. Rather than fearing students’ questions, I am learning to embrace them, and in particular those messy questions that are not easy to answer.

Inquiry in Practice

Let’s return to the scenario I’ve set out at the beginning of this article. I can’t claim to have come up with this activity—it is a classic of sorts—but it is a useful example to explain what I mean. The past several years I have used this activity early in the year with my 7th grade science students to help teach them some science process skills (predicting, hypothesizing, measuring, controlling variables, etc.) as well as to get them excited and motivated to learn more about God’s world. I find that this activity is a highly motivating and empowering way to get students to tap into their often-squashed curiosity that may have lain dormant in previous science classes.

About a week into the school year, I tell my 7th grade science students that they are about to participate in a lab activity, which is often enough to get them excited! I pull out five different brands of paper towels and set them in front of the students. Then I ask the Magic Question: Which brand is best? This is by nature a “messy” question, a subjective question. There is not necessarily one right answer. Yet I challenged my 7th graders to find an answer to this question, and even gave them three class periods to investigate, think critically, experiment, communicate, and justify an answer.

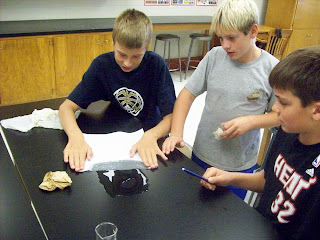

Students quickly begin offering suggestions—often based on T.V. ads or their family grocery-buyers’ preferences. As soon as everyone seems to have an idea in mind as to their paper towel preference, I turn students loose in the lab to begin trying to determine which brand is “best.” I have a variety of materials set out that might help them: balances, graduated cylinders, beakers of various sizes, droppers, funnels, rulers, and magnifying glasses. Students excitedly begin pouring water on tables and sopping it up, measuring, recording data in their notebooks, and arguing their respective cases.

This argument is actually the key to this activity. After letting students make a mess for fifteen or twenty minutes, I note the disagreement evident in our class about our paper towel preferences and ask a second Magic Question: What do we mean by “best?” This question often confuses students initially, but they soon realize just how fuzzy—and subjective—the notion of “best” really is. I ask students to argue their case as to what makes one brand of paper towels better than another. Students begin to offer many suggestions: absorbency, strength, durability, softness, appearance, and cost/value often top the list. This discussion draws out the idea that the term “best” is messy and subjective, and students will need to be more precise. It also brings up the key idea in doing inquiry: they’ll need to collect evidence to support their notion of which brand is the best. I then encourage pairs of students to determine how they will define which brand is best, and how they can test their predictions.

After a few more class periods to carry out their tests, I give students time to share their results in class, including their definition for the best brand, their predictions for which brands will be best, their procedures for testing, and the evidence they’ve collected to support their results. Predictably, students disagree about the results, because they have different definitions and different procedures for testing their ideas. This gives me a good opportunity to explain that this models the work of professional researchers—that the ground rules they set for their investigations largely determine the sort of procedures they will use and therefore the results they might obtain in their investigations. It also gives us an opportunity to discuss how we as Christians put our faith into action; that even when we disagree, we must be respectful and gracious to others. Through this processing, students come to understand that answers in science are not always cut-and-dried; a messy question is apt to have a messy answer as well!

To sum up, inquiry-infused science teaching involves engage students in answering testable questions. Through these questions, students begin investigating some aspect of creation. In the course of their investigations, students will make claims, and generate evidence to substantiate these claims. Finally, students communicate their findings to interested people, explaining their procedures and results.

Managing the Challenges of Inquiry-Infused Science

Teaching science this way has been a journey of discovery for me as well as my students. There are some real challenges that may need to be addressed if you seek to incorporate more inquiry-infused activities in your science teaching. Let me share a few suggestions:

First off, managing groups of students doing very different things can be a challenge. Because of this, I’ve had to develop clear procedures for start-up, materials maintenance, safety, and clean up—and teach these to my students! Also, it’s a rare case that I have 18 students doing 18 different things at once—I usually have students working as pairs or even quartets, which helps to limit the number of different things happening.

Second, inquiry-infused activities sometimes take more time than other approaches to teaching science. Thus, I’ve had to “prune” some non-essential topics from my science curriculum to give the time needed for students to explore and discover for themselves. It is true that I’m teaching less science content than I used to, but I would argue that I am actually teaching it better by infusing inquiry into my science classroom, because my students understand it better and actually remember what they have learned.

Finally, not every activity I do with my students has the level of open-endedness as the paper towel testing lab. I have begun to incorporate a range of inquiring activities into my science teaching practice. After all, even reading a textbook can become an inquiring activity if it is approached from a perspective of “let’s find out!” instead of “here’s what you need to know.” It is truly exhilarating to see students’ curiosity coming out in their questions as they investigate the world around them!

Conclusion

I have come to the realization that welcoming students’ questions is the foundation of modeling what science class is all about—coming to a deeper understanding of the creation and, by extension, the Creator. This shift has been challenging for me at times; when students ask questions, my first inclination is to answer them! I’m learning, however, to respond to a student’s question—even if I know the answer!—with something like, “Ooo, that’s interesting! How could we find out?” While this doesn’t always work, I’ve found students are much more engaged, more willing to ask questions, and more able to understand things at a far deeper level than they ever really did when I just “told them.”

You’ll notice that throughout this piece, I’ve tried to use the term inquiry-infused science instruction rather than inquiry-based. This is deliberate—I fully recognize that my classroom practice is not completely based in asking and answering questions. I am learning, however, to embrace the unknown and actively seek to engage students in asking questions that will guide their learning. As I’ve sought to infuse my science teaching with more inquiry, I’ve seen a direct correlation in my students’ motivation and interest in science, and my teaching has become more interesting as well. Allowing my students the freedom to ask questions with messy answers and then encouraging them to look for the answers has been an adventure in learning—for them, and for me as well.

No comments:

Post a Comment