I found this interesting, and challenging, because I tend to think that many of these methods are falling out of favor. Or at least, they are falling out of favor with me.

|

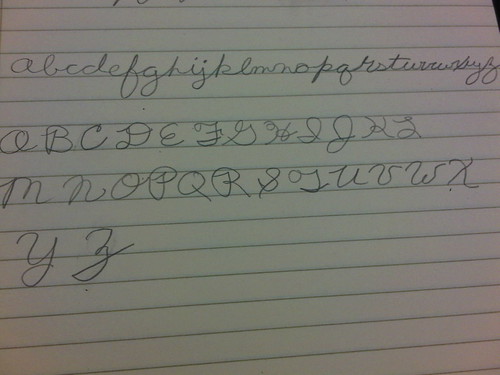

| Image courtesy Daphne Abernathy CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 |

I am a fan of teaching rhetoric; being able to construct a logically consistant argument is a key skill today as it was in yesteryear. And recitation seems to be a good thing in some situations, though I worry about the old around-the-world style reading aloud I remember from my elementary school days (30 years ago.) I'm just not sure that would really benefit a majority of students. Good oral readers are going to read well. Poor oral readers are going to read poorly. The public humiliation in that sort of activity doesn't seem worth any possible gain. On the other hand, reading aloud in a small group--or perhaps even just with a partner--seems like it might be a really good idea.

The one that troubles me the most here is rote memorization. I'm generally not in favor of rote memorization, unless it's in the service of understanding concepts. When I taught middle school science, I did have students memorize about 30 of the names and symbols of the elements on the periodic table. But that memorization was intended to help them understand formulas and how different elements combine. The memorization had a purpose beyond just memorizing the facts to spit them back on a test.

I suppose that's the argument about memorizing math facts, either by old fashioned flash cards or an iPad app--that the memorizing of the facts is pointed at understanding arithmetic concepts. But I wonder how often this is true? It often seems to me that memorizing math facts is just to be able to answer as many problems as quickly as possible: the dreaded "mad minute" timed test. I'm not sure that being a fast and accurate computer is the same as being thoughtful and understanding problem-solver.

I suppose that's also the argument about memorizing definitions of words, or lists of prepositions, or grammar rules. (I can still rattle off a list of prepositions I memorized in middle school, and I can still chant definitions my 5th grade teacher had us memorize for upper-level vocabulary.) But unless these lists are memorized to help students think deeply about concepts and skills, I'm not sure I agree with their value. Again, knowing the list is not necessarily the same thing as being able to use the vocabulary in writing, or understanding that one ought not end a sentence with a preposition.

Which prompts my question: Do old school methods promote understanding? Or just basic, low-level knowledge? Because if push comes to shove, I'm more interested in deep learning. I'm afraid some of these traditional (old school?) methods actually encourage shallow learning in this day and age. That may not have always been true, and it probably isn't true in all cases today. Old school methods certainly might help. Newer methods might help as well.

Old school methods might get in the way of deep learning. But, to be fair, alternatives to the old school methods might also get in the way of deep learning.

Whatever the methods are, the point should be deep learning. Learning for understanding. Learning for big ideas that transcend basic topics. Learning for more than minutiae to be memorized, regurgitated, and promptly forgotten.

We should be discerning about our methods. Let's be sure that our classroom practice truly reflects our philosophy of education. If we believe that depth of learning is key, whatever methods we choose must lead our students there!

No comments:

Post a Comment