But this title rings true for me.

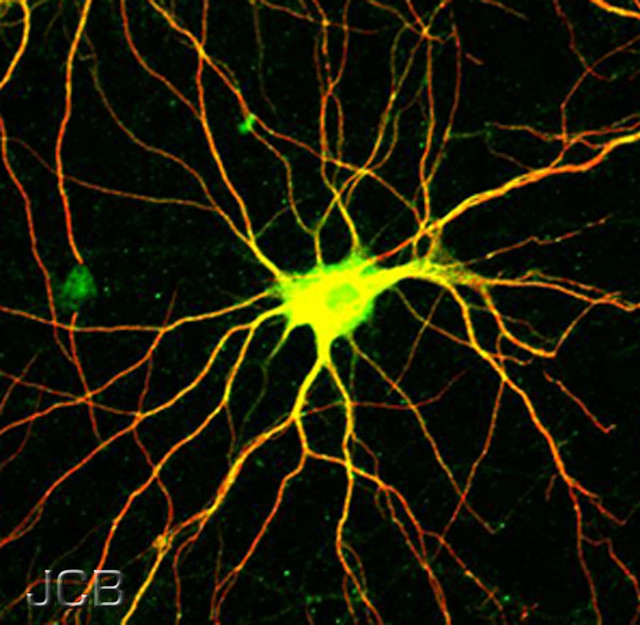

Dendrites, in case you haven't studied human anatomy and physiology lately, are the branches extending from neurons (nerve cells.) Every thought that you have is the result of electrical impulses traveling from one neuron to another, and it is the dendrites that allow for all sorts of communication to happen throughout the body as they connect the neurons. Each neuron can have thousands of connections to other neurons, and all of those dendrites matter for thinking and moving the body.

|

| Image by The Journal of Cell Biology [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0] |

So, here's the deal then. The argument being made in the title of the book is that simply completing a worksheet is not going to result in real learning--the "growing dendrites" part.

And that is the part that rings true for me.

Now, lest I sound so high and mighty, let's be real about this: I've assigned a lot of worksheets over my teaching career, so I'm pointing the finger at myself here first and foremost. In my defense, the longer I taught, the fewer worksheets I assigned...because I had a nagging feeling that they weren't doing what I thought they were doing.

Worksheets are often used to keep kids "busy" in school. But "busy" is not the same thing as learning. Can worksheets be used as part of a real learning opportunity? I think they can. I would like to think that some of the math practice sheets I assigned to my middle schoolers early in my teaching career were part of the learning that took place. I would like to think that some of the lab sheets I provided for my middle school science classes were part of the learning that took place.

Yes, I know that teachers are busy people with many, many demands placed on their time. And giving the kiddos a worksheet to do might give you a few minutes of peace to prepare for the next thing. I'm pragmatic enough to recognize that sometimes that is why a worksheet might be assigned.

But let's get this straight: a worksheet is not enough. A worksheet is not going to somehow magically produce learning in a student. It might be one part of a lesson, but just because a student has completed a worksheet does not mean s/he has learned anything!

If we're serious about "growing dendrites"--making connections, and fostering real, deep learning--we have to recognize the limitations of worksheets. If the purpose of the sheet is to keep the kids busy...well, okay...I've been there too... But let's not confuse being "on task" with being "engaged in learning."

Want a real-life example from my teaching practice? Okay, here's a short story:

When I was a middle school science teacher, I often spent some time at the beginning of 7th grade reviewing metric units of measurement. Yes, reviewing--these are things the kids supposedly "learned" in other grade levels, right? How many cm are in one meter, how many mL are in one liter, etc. And...I had a series of worksheets I assigned to give some practice converting different measurements into other units. The kids completed the worksheets (well...most of them did,) and thus I assumed that they had "learned" these metric measures, and had learned how to work with them and understand them.

HOWEVER...when we would actually try to use these different measurements in practice in our lab work, I found that the learning hadn't really "stuck"--they kids couldn't remember the conversions, and honestly, they couldn't always remember what the appropriate unit of measurement was.

After several years of this frustration, I had an epiphany: the worksheets were not working. The kids may have completed them...but they had not really learned these metric measures, and thus couldn't apply them to different situations when we were working in the lab.

So I changed tactics. Instead of the worksheet approach, we took time to actually, really use these different measurements. "How far is a kilometer? Let's actually take a walk during science class today and find out." Get out the trundle wheel, and the whole class hiked up the street to find out just how many "clicks" of the wheel it took to travel a km. "How much is a liter? Let's try to drink one during the school day tomorrow." Everybody had an empty 2L bottle, filled it halfway with water, and took an extra trip to the restroom by the time they came to my science class in the afternoon.

I tried to give them real life examples of the different measures:

- A millimeter is about the thickness of your fingernail

- A centimeter is about the width of your pinky

- A meter is a little wider than a doorway

- A gram is about the mass of one M&M

- A kilogram is about the mass of a 1 liter bottle of water

- A milliliter is about one dropperful

- A liter is half a 2L bottle :-)

And then, whenever we were going to be using these different measures, we would review our rules of thumb and name them specifically, and review, review, review...

Did they all remember them? Could they all make the conversions? Well, they still needed to practice them, sure. But compared to my former I've-given-them-a-worksheet-so-they-must-have-learned-this-stuff approach, they definitely learned more. Yes, they still needed practice. Yes, they still needed reminders. But they learned more.

And--dare I say it?--they enjoyed the learning all the more as well.

Because this is the point, teachers: no kid is going to be inspired to greatness by a worksheet. For real learning, we need real experiences, real opportunities to work with real materials, opportunities to practice (where a worksheet may be of some value), and a caring, dedicated teacher orchestrating these activities all along the way. Assuming that assigning a worksheet is going to foster this kind of dendrite-growing learning is missing at least part of the picture.

No comments:

Post a Comment